At StrengthSpace, many clients come to learn how to strength training safely with osteoporosis or osteopenia. They know their bones are fragile, and they know they should be doing something about it. “Loading” is what they are told to do. But many are told to avoid almost all the activities that cause this loading. It’s actually a touchy subject, because not all professionals agree on the best way to use exercise to address demineralized bones.

In this article, I want to provide a framework for how to think about addressing tissue weaknesses in general. This framework can be applied to osteoporosis, but also other musculoskeletal conditions (such as EDS or a chronic joint issue). The framework informs our approach at StrengthSpace, and it’s why our clients consistently show improvements on bone scans, often preventing the need for costly medications.

Why is strength training important for my bone health?

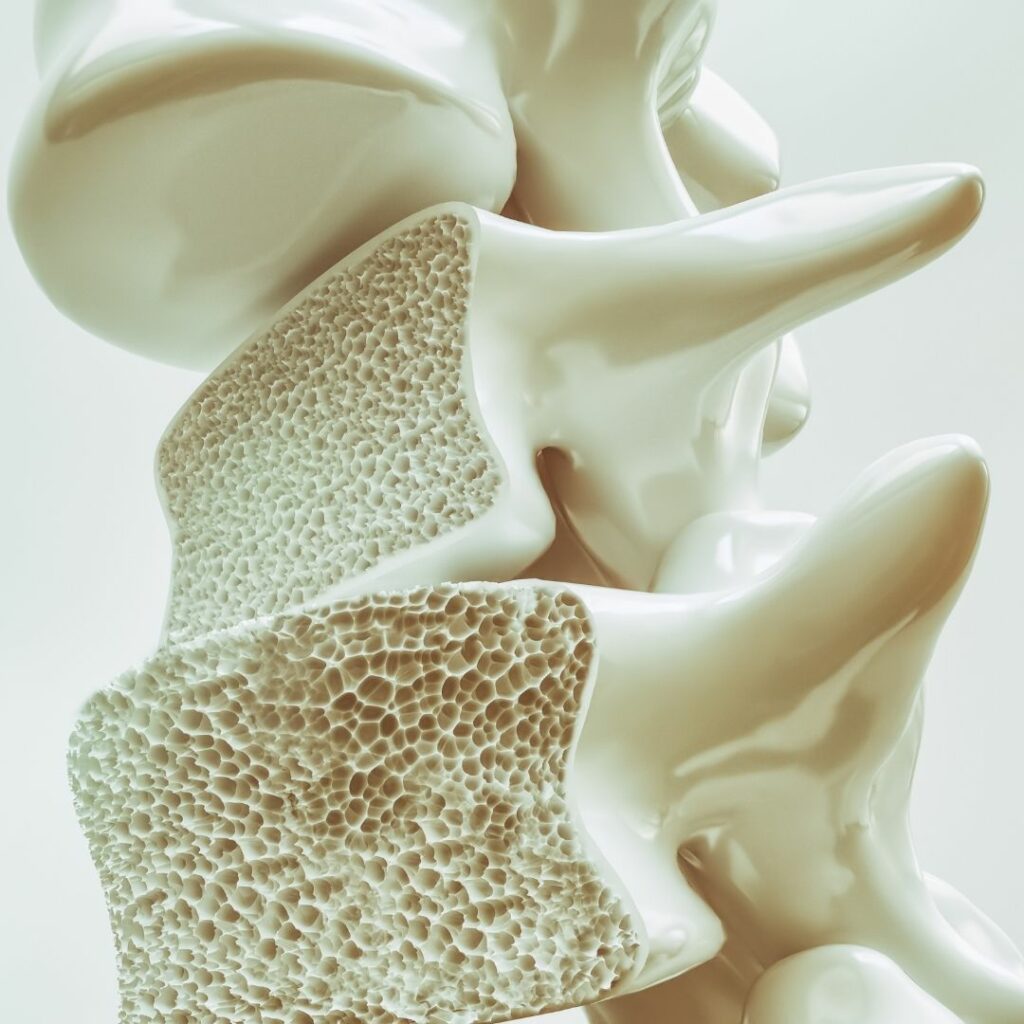

First, we need to discuss why we should be strength training. Now, we can’t make any guarantees that strength training will reverse any disease. But, there are many studies (i.e. this, this, and this) showing that resistance training should be a part of any management program for osteoporosis. Wolff’s Law is a medical axiom which states that bone will become denser where there is stress, and less dense where there is no stress. If we want stronger, denser bones, we must (cautiously) stress them with external loads.

On top of the benefits to the bones themselves, strength training reduces the risk of falls, and this is particularly true in people with osteoporosis. Crucially, muscle atrophy in the quadriceps muscle of the thigh is an independent predictor of falls. That means that, all else being equal, simply losing muscle in your thighs makes you more likely to fall and break a bone, which may be life-altering if you already have fragile bones. And the best way to prevent age-related muscle loss (sarcopenia) is through supervised resistance training.

How can strength training be safe if my bones are weak?

This is the challenging question. If our bones have poor tolerance to loads, how do we use loads to improve them? To help us wrap our heads around this, here’s the framework I mentioned earlier:

Anything that challenges the body is a “stress” on our tissues. If the dose of this stress is too high, we get damage. If the dose of this stress is tolerable, our bodies will adapt to it and form a protective response, or “adaptation.”

A stress can lead to damage, or protection. Friction can lead to blisters or callouses. Sunlight can lead to sunburns or tanning. Heat can lead to heat stroke or improved sweating and heat tolerance. Cold can lead to hypothermia & frostbite or improved thermogenesis and circulation.

And in the same way, the forces of our own bodyweight or external loads can cause strains or fractures if dosed too high. Or they can cause our muscles, tendons, and bones to thicken and strengthen when dosed appropriately.

In each case, it is the same kind of stress that produces either damage or protective adaptation. The difference is not in the *type* of stress, but rather in the dose. Strength training safely with osteoporosis is possible once we realize that the dose is what makes loading beneficial or harmful.

What if I’m afraid. Isn’t it best to play it safe and avoid any loading?

If you are vulnerable to a stress, it is smart to learn how to protect yourself (protective clothing from the sun, gloves to protect your hands, avoiding certain types of exertion day to day). But if you commit to NEVER exposing yourself to that stress again, you’ll actually become more vulnerable to it over time. Even if you stay active with moderate activities like gardening, it won’t be enough to load your bones sufficiently.

If you never go in the sun again, your skin will become even more vulnerable to burns. And if you never load your body in a certain way, such as overhead, your body will become even weaker towards that same stress. The answer lies in between – we need to employ protective strategies, but also deliberately apply a manageable dose of the stress to improve our tolerance.

With manageable doses we can safely improve our tolerance of stresses!

This might mean wearing a shirt and hat in the sun most of the time, but deliberately exposing yourself to small doses of direct sunlight to build tolerance. Initially, you might only go out in direct sun early in the morning for brief periods. But if you are methodical, slowly shifting your exposure window closer to mid day, and diligently monitoring the duration to prevent over exposure, then all but the most fair-complexioned individuals can see remarkable increases in their ability to tolerate direct sunlight. The same goes for callous building, heat-tolerance, or any other adaptation we might seek, and it is especially true for strength training to improve the health of our bones.

In fact, strength training is unique because we have so much control over the stress we are placing on our muscles and bones. By keeping track of the precise loads, range of motion, repetitions, and time under tension, we can record all of the variables that capture total stress on our muscles, ligaments, tendons, and bones. With this knowledge, we are able to begin with extremely light, safe, tolerable loads, and very cautiously increase our exposure to greater loads and for greater durations over our training career.

But I heard that you should never lift more than 10 pounds overhead.

We have to remember that if we want our bones to be stronger and more robust, we must expose them to the same qualitative stressors we are worried about, just at low doses which are safe. Often, you may read articles telling you NEVER to lift overhead, or to NEVER to load the spine. But the research tells us the opposite. Yes, sudden, heavy loading on the body can cause problems when we aren’t prepared for it. But studies consistently show that even very intense strength training can be safely tolerated by individuals with osteoporosis if the dosing is correct.

What we can take away from this is that the same activities which might be dangerous when done in the uncontrolled setting of every day life can actually be beneficial and therapeutic when done in a precisely measured manner, in a controlled environment, and supervised by a professional. This is a foundational concept in rehabilitation – take the dangerous thing, reduce it’s dose to make it safe, and then use repeated exposure to build up your capacity and robustness. And it especially applies to tissues that are very responsive to appropriate stress, like our muscles and bones.

It is true that an exercise like lifting weight overhead can be risky when you’re in your closet, trying to wrestle a heavy box down from a high shelf. The weight can shift, and your body can very suddenly go from “not loaded” to “heavily loaded.” Jarring forces like that can easily cause harm to fragile connective tissues. And this is why professionals (physicians, or physical therapists like myself) might recommend against overhead lifting or lifting more than a certain weight during your daily life. Like standing in the sun at high noon at the equator, this can be too much stress, too suddenly, and may overload your tissues.

The same load that is risky in daily life can be safe in a controlled environment,

But the exact same motions performed with a carefully selected weight, on a resistance training machine, are a different story. The slow increase in forces that you experience with careful uploading of the weight will expose your body to loads in a gradual way, free of sudden yanking or jerking. This is more like getting direct sunlight at 8am, for 15 minutes, twice per week. It’s a very safe starting point even for very fair skinned people, because the overall intensity is low, and the dosing carefully controlled to start to produce beneficial adaptations without suddenly overwhelming your tissues. Training using machines also allows even those with poor balance to challenge themselves without risking a fall.

The average clinician assumes you don’t have access to such a controlled environment. They are (justifiably) worried that you might go to a gym and lift too much weight, and with bad form. Since the risks of a big mistake are high, they know it’s safer to discourage you from doing these movements altogether. In that sense, their intensions are good! But I’d wager that they would endorse movements that load the spine, such as overhead exercises, if the following criteria are met.

- Safe Equipment

- Controlled Environment

- Professional Supervision

With supervision, you can strength train safely with osteoporosis.

The key takeaway here is: if you are unsure how to train safely, seek a professional. Work with someone who is experienced in supervising resistance training for people with connective tissue disorders like osteoporosis, where safety must come first. And when working with them, try to remember that activities that might normally cause blisters or sunburns might, in the right setting, and when dosed appropriately, help you get a protective tan and some callouses. Figuratively speaking of course!