This article started as a short post, and ballooned into a series. I realized there were key concepts I needed to explain about what makes an exercise “good” or “bad.” Now, it may be true that there are no “bad” exercises, but there are certainly exercises that don’t align with our goals. To identify the best exercises for those with Ehlers-Danlos, or for anyone who cares about their joints, what we need is a framework. In this article, I’ll describe the key factors I consider when working with clients with Ehlers-Danlos to determine if an exercise is a good fit for our goals based on safety, efficiency, and effectiveness. In subsequent articles, we’ll use this framework to identify the best and worst exercises for EDS (Ehlers-Danlos syndrome).

Our goals determine what is “Good.”

If your goal is to be able to do a handstand, then hand stands are the best possible exercise to (eventually) work into your program. If you want to be able to do a back-flip, then progressions for back flips are essential. But if your goal is just to build and preserve joint-stabilizing muscle mass in your arms and legs, then handstands and backflips are not wise choices. They aren’t “bad exercises” per se, but they do introduce a great deal of injury risk. And when compared to other options, they are very inefficient at sending a strengthening signal to our muscles.

This is why we need to be clear about what we want to achieve when evaluating the risk and reward of an exercise. Our goals determine whether the same exercise is an excellent choice, or risky waste of time.

Skill is specific, but muscle is general.

With the back flip, there is a huge amount of skill that must be mastered to correctly perform the exercise. A person might have to increase their muscle mass only modestly to be able to produce enough force to do a backflip, but they might have to master entire new motor skills. And the downside of the specific skill of backflipping is that very little of that motor pattern may transfer to other parts of your life, like lifting bags of much or carrying a grandchild.

A good golf swing doesn’t make you better at baseball. In the same way, a good back flip might not do much to improve your ability to run, climb, or carry heavy loads. A person who can already do a backflip likely has lots of coordination and explosive strength, but this doesn’t mean you or I will increase these attributes by learning to do a backflip. It may take a fast computer to run a video game, but putting that video game on another computer won’t make the computer faster at other tasks. Applied to us, a skill may require a lot of muscular strength, but that doesn’t mean learning that skill will increase our muscle mass.

The best exercises for Ehlers-Danlos are SIMPLE.

What we really want are adaptations (changes to our bodies) that are generally applicable – they help us with everything. Thicker muscles and tendons will make us stronger at everything. Denser bones will make us more robust to any fall. And more red blood cells and mitochondria will improve our stamina in any task. If we want an exercise to efficiently produce these generalizable adaptations, we want to minimize the skill needed to do the exercise. There is minimal skill involved in a wall-sit, and thus a wall-sit sends a very efficient strengthening message to the thigh muscles. It will make your legs better conditioned (more muscle mass and mitochondria) for everything you might need to do. This applies to any simple exercise involving continuous tension placed on muscles to safely cause fatigue.

Instability increases the skill demand, and the risk of injury.

One of the biggest factors that makes an exercise skill-based is instability. Squatting on a firm floor will let you get your hips and thighs pretty tired, but squatting on a swiss ball or wobble board actually makes it harder to achieve the deep fatigue we want. It may challenge your ankles, but long before your thigh muscles get deeply tired, you’ll start wobbling and have to get off the ball to avoid hurting yourself.

If you focus on unstable exercises like squatting on a ball, you will find that you get more skillful at those specific tasks, but see only mild increases in the strength and stamina of the large muscles in your hips and thighs. Or you might see that you get no additional benefit from the complex/unstable exercises, it just takes a lot longer to do them safely. You’ll have to keep getting off the ball, and it will take you quite a while to accomplish the same level of fatigue that a simple squat or wall-sit will create.

It’s not a great return on investment, especially when we factor in the potential for a serious injury that instability creates. When balance is a major feature of a strength exercise, even mild fatigue can lead to a loss of balance and a fall. This is simply a bad trade-off when the point of exercise in the first place is to increase our health and robustness.

The best exercises for EDS are STABLE.

To build more strength and stability for your hypermobile joints, I want you to prioritize stable exercises, where the supporting surface isn’t wobbling, and where you don’t have to worry at all about falling when you get fatigued.

These simple, stable exercises will allow you to push yourself towards a deep level of muscular fatigue SAFELY. You won’t need to stop when you start to wobble and lose your balance, and you’ll be able to get more productive training done in less time because it will be safe for you to let your muscles can really tired all in one go.

Exercises that go from easy to hard promote bad behaviors.

If an exercise has a really easy part, and a really hard part, guess where your body wants to spend the most time? Our bodies hate fatigue, and they’ll do anything to avoid it. Your muscles will burn, and you’ll feel an instinctive tendency to swing and bounce your weights to make the task easier. The personal training clients at our studio in Chesapeake, VA know how important it is to move slowly, and avoid bouncing, yanking, and using momentum. But this is easier to do when the exercise is well designed.

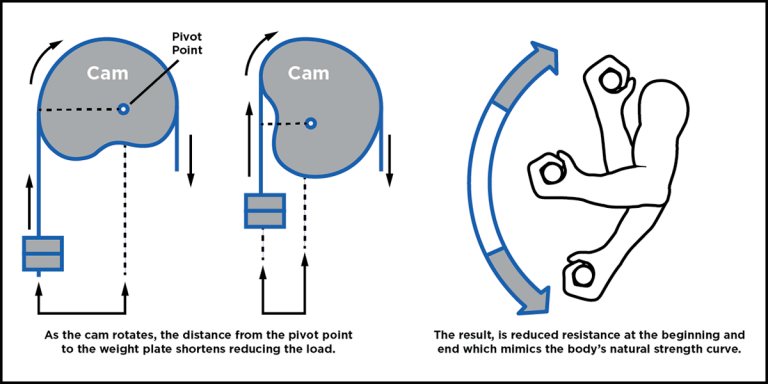

A poorly designed exercise lacks what we call “congruence.” A congruent exercise doesn’t have an easy part, or a hard part, because when you are strong, the resistance is high, and when you are anatomically weak, the resistance is lighter. This is one of the main insights that Arthur Jones had when he created his strength machine company, Nautilus, so named because the cams he designed, which allowed the resistance to vary throughout the movement, looked like Nautilus shells.

The best exercises for Ehlers-Danlos are CONGRUENT

When the resistance feels very “even,” or congruent, there is no easy part, and thus no hard part that you feel tempted to bounce or yank through. Research has actually shown that congruent exercises (termed “accommodating” in exercise physiology research) actually produce superior improvements in leg strength! Let’s consider some examples.

Traditional pushups and squats aren’t bad exercises. They aren’t unstable, or overly complex, but they do have poor congruence. They are both very easy at the top, when are arms and legs are locked out, and hardest at the bottom, when our muscles and tendons are stretched.

This incongruence we see in many traditional exercises like pushups and squats creates an almost irresistible urge to bounce out of the bottom and rest at the top. And this is always what you see during a military fitness test – people resting in the locked elbow position, and then bouncing furiously through the bottom of their pushups. All that bouncing allows you to do more reps, because you treat your tendons and ligaments like springs. But bouncing on a stretched-out joint is NOT a good idea for longevity, even if you don’t have a hypermobility condition like EDS!

This doesn’t mean we should never do pushups or squats. But it does mean we should always look for the most congruent exercises we can, which are usually machines with cams or leverage designs, and then we should modify bodyweight and free weight exercises when needed to improve their congruence, or compensate for their incongruence.

The best exercises allow you to build strength safely with Ehlers-Danlos

Most people with EDS understand that they need to build and preserve muscle mass without hurting their joints in the gym. But pain and fear of injury are the main reasons folks with EDS avoid exercise. That’s the tricky part of this – how do we ensure the muscles are getting stressed, not the joints? For starters, we pick exercises that make it easy to focus the stress on the working muscles, and avoid exercises that tend to promote bouncing, swinging, yanking forces on our tendons and ligaments. Any exercise that involves too much instability might force us into a position where our joints are vulnerable. And any exercise with very uneven resistance throughout the movement will make us want to cheat and bounce through the difficult parts, which leads to high forces on connective tissues.

The best exercises for EDS are simple, stable, and congruent. In the next article, I’ll give examples of the best and worst exercises using common equipment like swiss balls, dumbbells, and suspension trainers.

Could you please suggest some basic exercises that meet this criteria? Thank you

Hi Ashlee, yes.

First, isometric exercises like wall-sits, glute bridges, and planks on elbows (if tolerated by your joints) are all good examples.

Machine-based exercises on well-made machines can also be great options, though individual machines can vary for biomechanics.

And of course a suspension trainer *can* be a good option if used correctly. Here’s what I mean: Suspension Trainers for EDS