“Is exercise safe for my knees?” I get this question regularly from patients and strength training clients alike. It’s a reasonable question, given what most people (even clinicians) understand about osteoarthritis. In this article, I’m going to discuss the truth about arthritis and obesity, and how strength training can help. I’ll explain why the common focus on bodyweight and avoiding “wear and tear” is incomplete, and can lead people to miss out on the benefits of exercise for arthritis1.

First, here’s a quick summary of what we’re going to discuss.

- Osteoarthritis is NOT simply a “wear and tear” condition caused by too much load on joints.

- Osteoarthritis is driven by systemic inflammation and

- Blood sugar and hormone dysregulation, and visceral fat accumulation, drives systemic inflammation.

- Strength training reduces systemic inflammation directly, and by improving metabolic health.

- Strength training is also proven to safely improve pain and function in arthritic knees.

What is osteoarthritis?

Osteoarthritis (osteo – bone, arth – joint, itis – irritation/inflammation) is primarily characterized by thinning of the cartilage within a joint. Cartilage is amazing – it’s actually slicker than wet ice! It does an amazing job of eliminating friction when two bones have to move against each other under high forces. But when that cartilage breaks down, those bones experience friction due to the lack of protective cartilage. They experience significant stress, which can cause them to thicken and change shape to protect themselves.

As the bones inside our joints literally change shape, the joints start to behave differently. People can report hearing noises as they raise their arms or straighten their knees, and these can be unnerving. However, the evidence is pretty clear that exercise, and especially strength training2, is still highly beneficial for individuals with even the most advanced osteoarthritis. In order to understand why loading an arthritic joint can be beneficial, we need to dig into what really causes this breakdown in cartilage in the first place.

Osteoarthritis is driven by inflammation, not simply wear and tear.

Osteoarthritis (OA) is often contrasted with other joint disorders like Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) or its pediatric cousin, Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis (JIA). In these conditions, an active inflammatory and immune process targets and degenerates the cartilage and lubricating synovial fluid. The lack of targeted autoimmune action with osteoarthritis has led to a bit of a false dichotomy, even in the minds of many physical therapists, physicians, and other health care professionals. We have one category of arthritis that is “inflammatory” (RA and JIA) and another that is not (OA). While RA and JIA are driven by systemic disorders, OA is regarded as simply an issue of wear and tear.

But what if it’s not so simple?

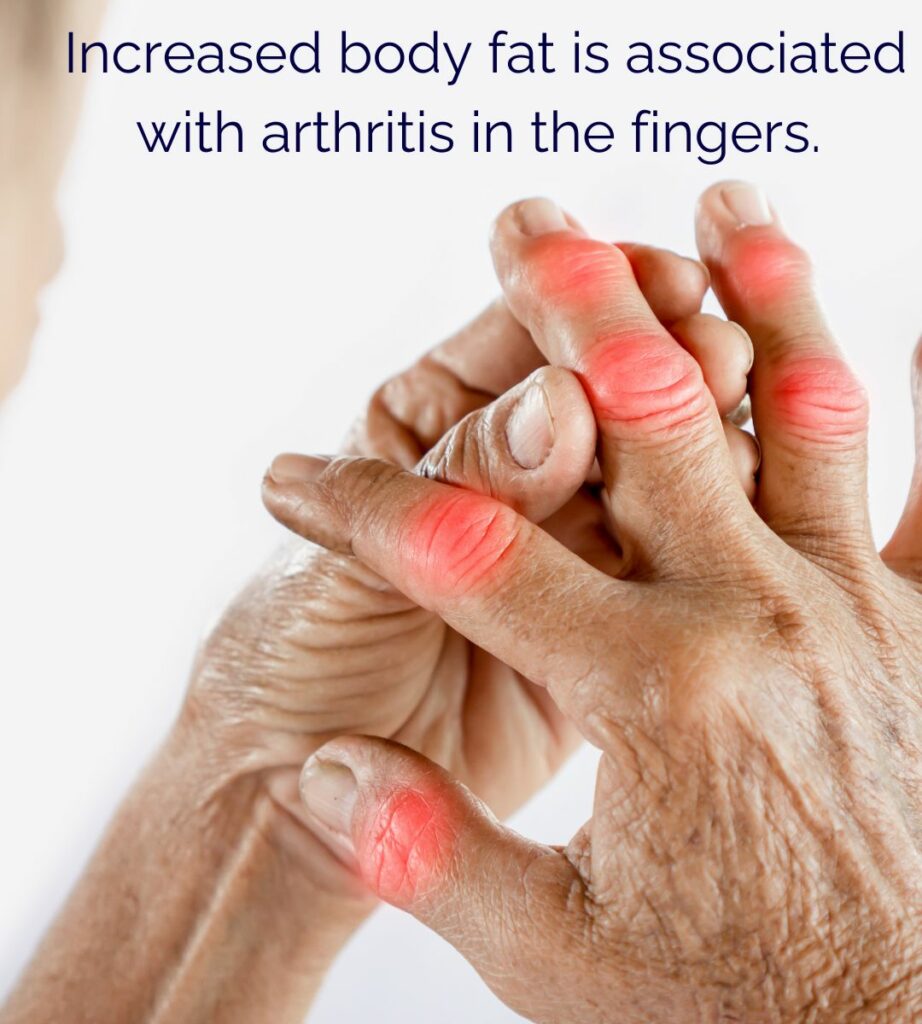

It comes as no surprise that arthritis is related to obesity. Added weight, after all, must drive more wear and tear, right? But a startling fact emerges: obese people have more arthritis in their fingers as well3. Unless we assume people are walking on their hands, we have to conclude that something else related to obesity must contribute to OA, besides weight. What’s more, even at normal bodyweight, people with more abdominal fat have a greater loss of function due to arthritis4. Something other than the weight must be driving the problem.

Evidence is quite clear that motion lubricates joints5. Being sedentary, even at a healthy body weight6, increases our risk of osteoarthritis. This simply could not be the case if the main thing that drives the development of arthritis is wear and tear. If that were the case, sedentary people would have less arthritis than recreational runners, but the opposite is true7! In fact, the amount of time you spend sitting and watching tv8 is an independent risk factor for developing arthritis! And in normal weight young people, the ratio of muscle to body fat is a better predictor of knee cartilage thickness than total body weight9. This is yet another indicator that weight and load through the joints is not the main driver of cartilage loss and OA development.

Of course, extreme levels of wear and tear also contribute to arthritis, and joint deformities and injuries obviously increase one’s risk for developing OA. But it is very clear that for most sufferers of OA, there is an inflammatory process that ages our synovial tissues10 and leads to a loss of cartilage thickness. Inflammation is the issue, and as we’re about to find out, where we have stored body fat may be a better indicator of our levels of inflammation than how much we weigh.

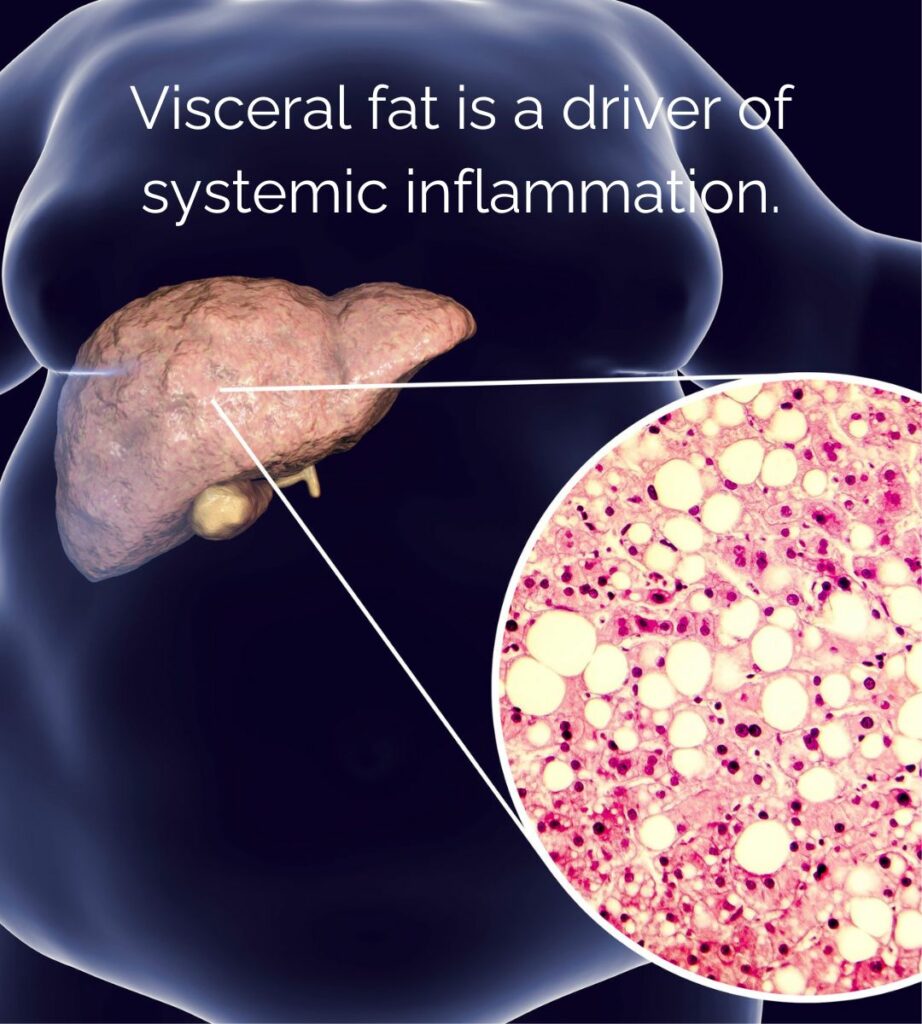

Visceral fat is a major driver of inflammation.

This gets a bit technical, but digging into the truth about obesity and arthritis is critical if we want to understand how strength training can help.

Generally, our bodies have a limited ability to store extra calories as body fat. Some people can’t store much fat, while others can grow many new fat cells in order to store extra calories. In a way, this ability to increase fat stores is actually protective. Once we run out of room in our subcutaneous fat (the fat cells under our skin), we then start to store the fat in our muscles and organs11, as “visceral fat.” This is when excess fat becomes enormously damaging, as both fat infiltration in muscle12, and fat in and around the liver, are strong indicators of metabolic disease and cardiovascular risk13.

Regardless of whether a person runs out of storage capacity after gaining 20lbs of fat or 200, the result is a major increase in systemic inflammation. Once our fat cells become full to capacity, they start releasing messenger molecules called inflammatory cytokines, such as Interleukin-6, and Tumor Necrosis Factor alpha. This process then becomes even more accelerated as we start storing more fat around our organs and within our muscles.

Inflammatory cytokines normally only elevate in response to acute stresses, which include anything from the normal wear and tear of demanding exercise, up to an injury or illness. And ideally, they lead to a healthy healing response. But if these compounds are chronically elevated in the bloodstream, the body begins to become numb to their effects, not unlike the way we can become resistant to insulin or leptin. The signal to begin healing cartilage in response to stress gets lost in the noise of systemically elevated inflammatory chemicals.

It’s important to emphasize the nuance of what is really going on here. Added weight isn’t friendly to joints, but the real problem is the systemic inflammation and metabolic damage that develops when our body begins to accumulate visceral fat14, and fat in muscles15. In fact, one of the signs that this process is malfunctioning is elevated blood sugars, and it turns out that this too is a significant risk factor for the development of arthritis16. When blood sugars become badly dysregulated, a person is diagnosed with type 2 diabetes, a disease caused by elevated but dysfunctional insulin signaling. Type 2 Diabetes significantly exacerbates the progression of osteoarthritis17 by driving chronic inflammation.

If only there were a way to address metabolic dysfunction …

Strength training helps reduce systemic inflammation.

This is the key insight on the truth about obesity and arthritis: we should worry less about wear and tear, and more about strength training to help our symptoms and metabolic health. OA is a disease of insufficient healing caused by inflammation. We also understand that managing the inflammation, and not avoiding load, should be our primary focus when trying to slow its progression and alleviate symptoms. This is where strength training can play a key role.

Exercise in general, and specifically strength training, exerts powerful anti-inflammatory effects18 in the body. Increasing motion through exercise causes muscles to release anti-inflammatory chemicals that direct improve cartilage health19. Strength training can help mitigate metabolic dysfunction by promoting adequate muscle mass, reducing visceral fat, and depleting muscle glycogen. With a healthier metabolism (normal blood sugars and insulin levels), we are less likely to suffer the negative consequences of systemic inflammation on our joints.

On top of this, strength training significantly reduces visceral fat20 when performed consistently. This is likely due to the improved glucose disposal, insulin sensitivity, and basal metabolic rate that results from improving our muscle mass through strength training.

No discussion of reducing inflammation would be complete without also discussing other factors, several of which may be even more important:

- Sleep: Poor sleep quality drives poor immune function21, metabolic disease, and systemic inflammation22. Here is my advice on getting better sleep.

- Nutrition: This is a complex topic, and I advise you to work with a professional like Kelly at ThinkWellNutrition.com. Suffice it to say that a protein rich, whole foods diet helps to prevent overconsumption of calories, thus minimizing the risks of metabolic dysfunction and visceral fat accumulation.

- Sun Exposure: Lower Vitamin D levels are associated with a greater risk of osteoarthritis in younger people, with the lowest levels associated with the most severe OA. Further, sunlight is also used to produce much of the body’s Nitric Oxide, a critical regulator of endothelial function23 (blood flow). Getting very little sunlight leads to low levels of nitric oxide, which can promote systemic inflammation and exacerbate vascular damage from diabetes24.

All these factors have profoundly synergistic effects. Paying attention to our sleep, nutrition, and other lifestyle factors like sun exposure will also help directly enhance the benefits we’ll get from strength training.

Strength training is safe and effective for managing osteoarthritis

It’s probably more helpful to actually make this point from the other direction. NOT strength training is actually quite dangerous for people with OA. Being weak is quite literally one of the most dangerous risk factors a person can have. Strength training can help as avoid becoming frail, which is an indicator of our risk for falls25, a major driver of disability and death in the elderly. But also, how much muscle mass we carry actually affects our likelihood of developing, or worsening, osteoarthritis.

In one study, researchers found that both low muscle strength AND low appendicular lean mass, or the amount of muscle mass on our limbs, were strong predictors of the development of knee osteoarthritis26. Another team of researchers was also very clear that we can’t just train around the problem – the arthritic joint needs to be strengthened directly:

“Therefore, rather than weight loss alone, the quadriceps muscle and the rear-thigh muscles, which maintain the stability of knee joints during rehabilitation training, should be strengthened emphatically to improve muscle mass.”27

Relationship between Knee Muscle Strength and Fat/Muscle Mass in Elderly Women with Knee Osteoarthritis Based on Dual-Energy X-Ray Absorptiometry – PubMed (nih.gov)

And beyond just promoting healthy muscle mass, strength training also improves proprioception, or the ability of the nervous system to control joint position. In a systematic review with meta-analysis of other studies, researchers at the Exercise and Rehabilitation Sciences Institute of the Universidad Andres Bello in Chile showed that strength training significantly enhanced various measures of proprioception. This may explain why other similar systematic reviews have shown that strength training improves gait speed, function, and pain in people with osteoarthritis28.

The lesson here is clear. Using strength training to prevent and reverse age related muscle loss can significantly improve outcomes for people with osteoarthritis. If our joints have less cartilage, they need as much muscular shock absorption as they can get. Becoming weaker by playing it safe and staying on the couch will only exacerbate the problem.

Conclusion and References

Now we understand the link between obesity and arthritis, and how strength training can help. Proper sleep, nutrition, adequate sunlight and activity, and proper exercise are the foundation of low-inflammation living. Strength training may not be the most important of these, but it definitely takes the least will-power to get right. Stimulate the muscles of your hips and thighs with a high degree of effort, using techniques and equipment that allow you to minimize force and avoid unnecessary joint stress. Do this every week, and your body will benefit from the powerful anti-inflammatory effects of deeply fatiguing your muscles. Stay consistent, and the strength increases you will experience will drastically improve your functional capacity, and your muscular quality – an essential element in preventing and managing joint pain.

- Strength Training vs. Aerobic Training for Managing Pain and Physical Function in Patients with Knee Osteoarthritis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis – PMC (nih.gov) ↩︎

- The Role of Resistance Training Dosing on Pain and Physical Function in Individuals With Knee Osteoarthritis: A Systematic Review – PubMed (nih.gov) ↩︎

- Adiposity and hand osteoarthritis: the Netherlands Epidemiology of Obesity study – PMC (nih.gov) ↩︎

- Normal Weight with Central Obesity, Physical Activity, and Functional Decline: Data from the Osteoarthritis Initiative – PMC (nih.gov) ↩︎

- Range-of-motion affects cartilage fluid load support: functional implications for prolonged inactivity – PubMed (nih.gov) ↩︎

- Causal effect of physical activity and sedentary behaviors on the risk of osteoarthritis: a univariate and multivariate Mendelian randomization study – PMC (nih.gov) ↩︎

- The Association of Recreational and Competitive Running With Hip and Knee Osteoarthritis: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis – PubMed (nih.gov) ↩︎

- Causal association of leisure sedentary behavior with arthritis: A Mendelian randomization analysis – PubMed (nih.gov) ↩︎

- Ultrasound measurement of femoral cartilage thickness in the knee of healthy young university students – PubMed (nih.gov) ↩︎

- Identification of aging-related biomarkers and immune infiltration characteristics in osteoarthritis based on bioinformatics analysis and machine learning – PubMed (nih.gov) ↩︎

- Visceral Fat and Diastasis Recti – StrengthSpace (strength-space.com) ↩︎

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30852623 ↩︎

- Obesity Phenotypes, Diabetes, and Cardiovascular Diseases – PubMed (nih.gov) ↩︎

- Obesity, Adipose Tissue and Vascular Dysfunction – PMC (nih.gov) ↩︎

- Myosteatosis: What is Fatty Muscle Disease? – StrengthSpace (strength-space.com) ↩︎

- Glucose Homeostasis Influences the Risk of Incident Knee Osteoarthritis: Data from the Osteoarthritis Initiative – PMC (nih.gov) ↩︎

- Type 2 diabetes mellitus and osteoarthritis – PubMed (nih.gov) ↩︎

- Effect of exercise training on chronic inflammation – PMC (nih.gov) ↩︎

- Exercise induced meteorin-like protects chondrocytes against inflammation and pyroptosis in osteoarthritis by inhibiting PI3K/Akt/NF-κB and NLRP3/caspase-1/GSDMD signaling – PubMed (nih.gov) ↩︎

- Effect of resistance training with and without caloric restriction on visceral fat: A systemic review and meta-analysis – PubMed (nih.gov) ↩︎

- Sleep and inflammation: partners in sickness and in health – PubMed (nih.gov) ↩︎

- Relationship of Chronic Systemic Inflammation to Both Chronic Lifestyle-Related Diseases and Osteoarthritis: The Case for Lifestyle Medicine for Osteoarthritis – PubMed (nih.gov) ↩︎

- The paradox of nitric oxide in cirrhosis and portal hypertension: too much, not enough – PubMed (nih.gov) ↩︎

- Impact of ultraviolet radiation on cardiovascular and metabolic disorders: The role of nitric oxide and vitamin D – PubMed (nih.gov) ↩︎

- A Review on Aging, Sarcopenia, Falls, and Resistance Training in Community-Dwelling Older Adults – PubMed (nih.gov) ↩︎

- A Bidirectional Mendelian Randomization Study of Sarcopenia-Related Traits and Knee Osteoarthritis – PubMed (nih.gov) ↩︎

- Relationship between Knee Muscle Strength and Fat/Muscle Mass in Elderly Women with Knee Osteoarthritis Based on Dual-Energy X-Ray Absorptiometry – PubMed (nih.gov) ↩︎

- Effect of strength training on knee proprioception in patients with knee osteoarthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis – PMC (nih.gov) ↩︎