Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) gets very little air-time despite the huge number of women it affects. Many of my own clients struggle with it, and I’ve wanted to to write about it for years. And while I am not qualified to do a deep-dive on the entire pathophysiology and treatment of this condition. I can discuss it from the perspective of exercise. At no point will I imply that PCOS or any other medical disorder can be “fixed” by exercise. But I will make the case that training with high intensity, both with strengthening exercises and interval training, is especially beneficial for those managing PCOS.

Quick Summary

- PCOS often involves excess insulin, which can disrupt normal ovarian function.

- Our muscles are like sponges for the sugars in our diet, capable of storing them as glycogen.

- When our “sponges” are full, we produce more insulin to manage dietary carbohydrates.

- Brief but intense sprint/interval training can “wring the sponges out,” depleting muscle glycogen and reducing the insulin levels.

- By keeping exercise quantity low, sprint intervals avoid the problems of amenorrhea often caused by chronic over-exercising.

What is PCOS?

Polycystic Ovary Syndrome impairs the function of the ovaries: specifically their ability to ovulate and to correctly produce sex hormones. PCOS is often diagnosed based on a combination of: ultrasound examination of the ovaries, assessment of menstrual cycle regularity, and measurement of male sex hormones like testosterone (yes, women produce these as well). Women with PCOS can suffer a number of difficult symptoms, and can struggle with fertility.

Insulin and PCOS

A consistent finding in women with PCOS is disrupted insulin signaling in the body. Insulin, if you recall from my other articles, is a messenger hormone released by the pancreas which helps control the amount of energy circulating in the blood.

When we take in food energy, especially as carbohydrates, our pancreas releases insulin to tell our body how to respond, much like a police officer directing traffic:

Our fat cells “hear” this insulin message by withholding the release of fatty acids. Our livers “hear” this message by shutting down the creation of sugar (glucose). And our muscles and other tissues “hear” this message by increasing their own absorption of sugars for storage or to be burned as energy.

Glucose is a highly reactive molecule which can damage blood cells and vessels if it is too concentrated, and can feed bacterial infections. Accordingly, this whole insulin signaling process is designed to keep blood sugars in a controlled range by quickly move incoming carbohydrates out of the blood stream so they can’t get up to any mischief.

Many women with PCOS are insulin resistant and at risk for diabetes.

In many women and adolescent girls with PCOS, insulin fails to convey its message to the tissues. Their bodies produce insulin, but the tissues don’t “hear” the message clearly, which requires the pancreas to speak “louder” by producing more insulin. When the pancreas increases its production of insulin, but the body’s tissues have a reduced response to insulin, this is called insulin resistance.

If this process sounds suspiciously like the very beginnings of type 2 diabetes, that’s because they are one and the same. Many women with PCOS demonstrate insulin signaling very similar to that seen in pre-diabetes, even if their blood-sugars are currently normal. And according to one systematic review paper, women with PCOS are 2-3 times as likely to develop gestational diabetes, and 3-8 times as likely to develop type 2 diabetes, as women of the same weight but without PCOS.

The link between elevated levels of insulin in the blood and increased testosterone production by the ovaries is so clearly demonstrated in research on the subject that many scientists consider the elevated insulin to be a major contributing factor, if not an outright cause, of PCOS. The direction of causality is very hard to establish here, because it is (obviously) ethically impossible to do a study which attempts to directly cause PCOS in humans through the administration of insulin. But what we can conclude is that normalizing insulin levels in the bloodstream and insulin signaling in the tissues is likely to be highly beneficial to these women.

Why should we consider high intensity exercise for PCOS?

And this is high intensity sprint-interval training starts to matter for PCOS. Muscles store a modest amount of glucose (aka carbohydrate or “sugar”) as an emergency fuel source called glycogen. And as I’ve discussed here, a muscle that is already full of glycogen is less willing to absorb extra glucose when insulin is present. But by deliberately depleting our glycogen stores with high intensity sprint-style interval training we can increase our sensitivity to insulin.

This idea of “wringing out the sponge” is helpful because, despite the extremely small time-commitment, as little as two sprints can deplete muscle glycogen by over 20%, and increase our muscles absorption of blood sugar (measured by GLUT-4 receptor expression for my fellow nerds) for hours after training.

This means our pancreas will need to produce less insulin to manage our blood sugars after our next meal, which can lead to a reduction in circulating insulin. Getting insulin back to normal levels may be an important contributor to getting the ovaries to produce normal levels of testosterone.

"Women with PCOS should be encouraged to engage in vigorous aerobic exercise or resistance training to experience their insulin-sensitizing effects." Mussawar et al, 2023.Does the intensity of exercise matter for improving insulin sensitivity?

In short, yes. Our bodies store copious amounts of fat (weeks to even months worth of energy), which we can use to fuel very long bouts of low to moderate effort activity. However, we only store small amounts of glycogen – barely enough to sustain us for a few minutes of truly maximal effort exertion. Our bodies are smart, and they tend to reserve this “emergency” fuel source for extremely high effort activity. Think sprinting for your life, or wrestling an attacker!

This is why intensity matters. Plodding at low to moderate intensity on the treadmill for 45 minutes might barely make a dent in our glycogen levels. In fact, one study showed that large amounts of muscle glycogen remain after up to 3 hours of low intensity cardio (cycling), whereas training at a “supramaximal” (or above sustainable pace) effort yielded 5-7 times as much glycogen depletion in much less time.

Max-effort sprint intervals deplete glycogen in just minutes per week.

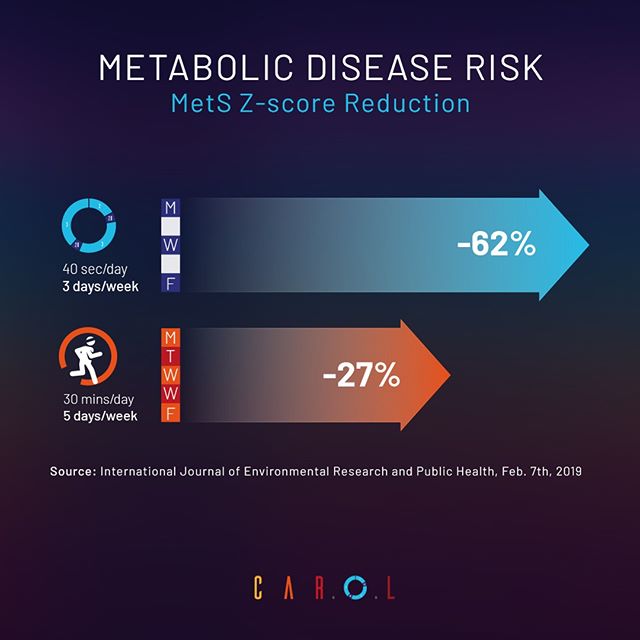

By contrast, just a few sprints can significantly deplete muscle glycogen, and trigger an entire cascade of beneficial adaptations. In one study, just 4 sprints performed 3 times per week (30 total minutes per week including rest breaks) yielded the same benefits to fasting insulin and insulin sensitivity as 30 minutes of brisk aerobic exercise performed 5 days per week (150 total minutes per week).

Another study showed that just two weeks of sprint cycling improved insulin sensitivity by 26%! Participants did 4-6 sprints, 3 times per week. Even with long rests between sprints, each workout took about 20 minutes total.

And in yet another study, participants who rode an exercise bike 3 days per week, for three 20 second sprints performed over 10 minutes yielded the same benefits to fitness, body composition, and insulin sensitivity as 50 minutes of moderate intensity riding. That’s 1/5th of the time commitment for the same benefits.

They key with all these is the intensity of effort. By pushing yourself to work as hard as you can against the resistance of an exercise bike (or through another “cardio” modality like rowing, versa-climbers, etc), you will force your body to quickly burn through your muscles’ glycogen stores, enhancing your insulin sensitivity, and potentially lowering your circulating concentration of insulin.

And this study isn’t alone. Other studies show a clear edge for certain health parameters when high intensity training is performed for PCOS. In fact, sprint intervals improved metabolic health even without weight loss in women with PCOS.

Traditional “cardio” won’t reverse insulin resistance in women with PCOS.

If you already engage in lots of low-intensity activity, like walking or swimming, it can be tempting to think “I do enough,” and not pursue higher intensity training. But while remaining physically active is a good thing in general for metabolic health, the research clearly shows unique benefits to max-effort sprint training that can’t be recreated by any amount of low intensity activity. In fact, for insulin-resistant women with PCOS, a systematic research review showed that longer bouts of low effort training simply weren’t sufficient to cause the benefits we are seeking.

Moderate aerobic exercise appears to be insufficient to induce any beneficial effects on fertility in this population

Mussawar et al 2023

The reasons for this are complex. It may have something to do with the tendency of longer sessions of cardio to increase our appetite, leading to compensatory over-eating. High intensity training, by contrast, has the paradoxical effect of helping to control our appetites. This can be seen both subjectively, and when we directly measure the hunger hormone ghrelin after sprint training! And as I showed earlier, if glycogen depletion is the goal, longer efforts are often not demanding enough to force our bodies to tap into “emergency” fuel, and simply don’t deplete glycogen efficiently enough.

Too much exercise can impair reproductive function.

Here is another reason longer bouts of steady-state exercise aren’t optimal: they require too much exercise volume.

Exercise is a negative stress – it’s something our bodies don’t “like.” Much in the same way that our bodies build a callus against something they don’t “like” (friction), our bodies build a host of responses (stronger muscles and bones, more red blood cells), to protect against the negative stress of challenging mechanical work.

And like any stress, it can be easy to over-do things if we fail to dose the stress correctly. The evidence is abundant that over-exercising can result in amenorrhea (loss of period). After all, menstruating is an expensive process, requiring lots of resources from the body. And as Herman Pontzer describes in detail in his excellent book, Burn, very often our body can simply adjust its metabolic rate downwards in response to excessive amounts of exercise. Or worse, it can adjust our hunger upwards dramatically to compensate.

In other words, doing lots of moderately intense exercise can create an energy deficit, and instead of simply getting leaner, the body can preserve its fat for emergencies, and shut down other expensive processes instead, like the reproductive system!

High intensity training for PCOS helps us to avoid over-exercising.

This is why exercising at higher intensity actually makes it easier to avoid overdosing on the quantity of exercise. By performing just 2-3 maximum effort sprint intervals a few times per week (4-8 total sprints per week!), we can realize dramatic benefits to our body composition, metabolic health, and quite possibly our fertility and sexual health.

The Carol AI bike we use at StrengthSpace takes all of the guess work out of this process, especially with respect to how many sprints to perform, and how much rest to take. And because the resistance is precisely selected by the AI algorithm, you’ll be training at a high enough intensity to deplete your muscle glycogen, which is crucial for PCOS. If you don’t have access to a CAROL bike, an assault bike, or any piece of cardio equipment can work. I’d err on the side of keeping your bouts of effort short (2 to 4 bouts of 30″ or less), working at the highest level of effort possible, and taking adequate rest between sprints to feel fully recovered.

Conclusion

It can be tempting to stick with what feels good, and avoid what feels hard or uncomfortable. And while we should try to find forms of exercise we feel are sustainable, we must also accept that there is a certain degree of stress and discomfort we’ll need to endure if we want our bodies to build more fitness and improve their health. As I said, we are trying to get our bodies to burn “emergency” fuel (glycogen), and the efforts needed to force that must be high.

It goes without saying that you should never undertake any exercise regimen to address or manage a medical condition without first consulting your qualified health care provider. After you do that, work to find a coach you can trust with experience working with your condition, who can guide you through the process of working at the right level of effort safely.

When I applied for your open EP position, this training caught my eye. Metabolic Health is the space I currently coach, focusing more on nutrition.

Imagine the results for women if they decrease the insulin response to food and depleted glycogen stores through HITT.

Hi Kelley, thanks for your comment, and I agree they are a powerful combination.