As our personal training clients know, strength training is an essential part of our road back from an injury or surgery. During our rehab, and for general health, strength training is how we build the muscle mass and connective tissues lost to disuse. But did you know that you can actually improve the outcomes of a scheduled procedure by strength training before surgery?

Your joints aren’t a “lost cause.”

If you have been told you need surgery, you may be tempted to hold off on exercise. This is even more likely if you are having a surgery to replace an arthritic joint. Perhaps you are scheduled for a knee replacement, and you think it pointless to try and build strength around your knee since it is going to be replaced anyway. You may fall into the trap of thinking that your joint is a “lost cause”, and you tell yourself: “I’ll rebuild after I recover from surgery.” Or worse, you may think that training your leg muscles with weights will actually increase your pain and swelling, or hurt your joint further.

These concerns are very natural. And very wrong.

Remaining active does not make your arthritic joint worse. Instead, it actually improves your body’s ability to quickly recover from surgery. To understand why, let’s think about how our bodies respond to disuse…

Being sedentary weakens cartilage faster.

Intuitively, you might think that it is best to rest an arthritic joint. But it isn’t. Losing muscle and avoiding loads on your joint cartilage have both been proven to accelerate the progression of arthritis. Muscle responds to loading (exercise and activity), and if you lose that muscle, your body can’t shock-absorb as well, leading to greater strain on the joints. But more surprisingly, cartilage responds to loading too. Provided you don’t injure your cartilage with overuse or very high impact activities, keeping some load on the cartilage stimulates it to be healthy, just like every other tissue in your body. When we remove that load entirely, studies have shown that the cartilage gets thinner faster.

This means the last thing you want to do is become sedentary and weak when you are told you have osteoarthritis in a joint.

Instead, it is in your best interest to get as strong as you can while avoiding injury. By safely building strength in the muscles around your arthritic joint, you add protection to the joint, stimulate the cartilage to be healthy, and may even postpone your joint replacement.

More muscle before surgery means more strength after.

Think of your muscle mass as a savings account for emergencies. During any hospitalization, we have to live off our “muscle savings account.” The forced period of inactivity leads to muscle wasting as our bodies start downsizing underutilized tissues. In fact, just ten days of bed rest will result in several pounds of muscle loss, even in healthy young adults! Given that some muscle loss is inevitable, we want to start with as much as we can. The more muscle you start with, the more you’ll have leftover once you finally get moving again.

Many surgeries involve down times of weeks to months afterwards, during which your ability to use your muscles is greatly limited. And during that time, muscular atrophy is inevitable. Knowing this in advance, we should seek to build as much muscle as we can with strength training before surgery. This way, even if we lose 20 or 30% of our muscle from disuse, we will still end up with more total muscle than if we had not built up a reserve.

And luckily, we don’t have to settle for simple logical deductions in making my case for strength training before surgery. Many studies have sought to answer this exact question, and they show a clear relationship between getting strong before your procedure and better recovery afterwards.

Strength training before joint replacement means better function after.

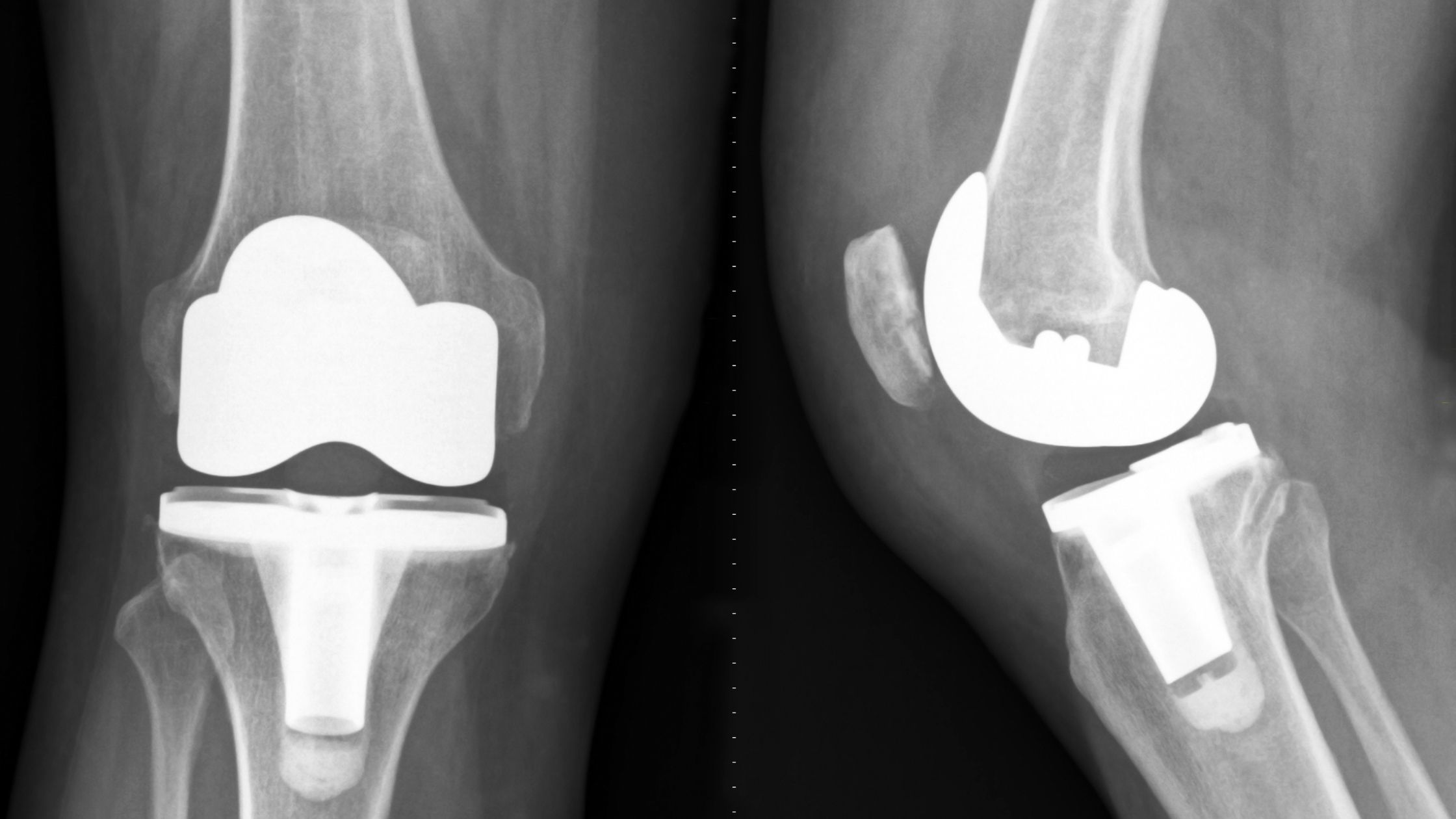

Knee replacements are particularly well-studied in this regard. Unlike the simple ball-and-socket of the hip, knee mechanics are a little more complex. More muscular coordination is required to control the tibia, femur, and patella as we use our knees to ensure proper tracking and alignment.

Because of this greater need for muscular control, it should come as no surprise that the strength of the muscles around the knee is a significant predictor of function for things like walking speed, and the ability to rise from a chair without the use of your hands. And of course, individuals who engage in strength training prior to knee replacement do all of these tasks better than those who don’t. They walk faster, climbs stairs more easily, and are better able to stand from chairs than individuals who “took it easy” and avoided exercise prior to their surgeries.

Strength training before knee replacement surgery also reduces pain and makes rehabilitation more effective. Amazingly, these effects can be seen up to a full year later. Even at 12 months after knee replacement, patients who had done strength training before surgery had stronger quadriceps (thigh) muscles than patients who had not, despite the same rehab after surgery!

These benefits apply to other forms of surgery as well. Even patients scheduled for major lung surgery saw benefits to strength training. In one study, patients who did preoperative strength training had regained more functional endurance 3 months later, when compared to those who did no strength training before surgery.

More muscle mass means a shorter hospitalization.

If you know you are going to be hospitalized for a surgery, you want to do everything in your power to minimize your length of stay. Leaving aside the fact that it is hard to eat well on hospital fare, the inactivity of being in the hospital leaves us deconditioned, which slows down our recovery. And when we look at factors that tend to prolong hospitalization, low muscle mass is a major concern. Strength training reduces length of hospital stay in total joint replacement patients, and even in cancer patients scheduled for surgery!

In one study of patients scheduled for heart surgery, the thickness of muscles around the spine was a strong predictor of whether the patients went on to suffer complications which prolonged their hospital stay. This is consistent with other studies showing that people with thicker muscles are less likely to suffer illness and death. Simply put, having thicker muscles makes us more robust, which means we bounce back faster for major health stressors like surgery.

The more muscle you are left with after your acute recovery phase, the more you have to build on as you start to rehabilitate yourself. Stronger muscles make rehabilitation go more smoothly and result in a higher level of function. They can make the difference between regaining the ability to hike and climb stairs, versus barely regaining the ability to walk unassisted.

Preoperative Strength Training Benefits Serious Injuries Too!

Most people can buy into the idea that strengthening an arthritic knee can improve outcomes after joint replacement. But when we look at acute injuries, it’s a harder sell. Surely a joint with a badly torn ligament should be left to rest, right? Wrong. While our instincts may suggest that a painful, swollen joint should be left completely to rest before surgery, the evidence shows that we should do the opposite. Strength training before surgery, even with a torn ligament like the Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL), will improve surgical outcomes and functional performance.

One team of researchers found that in patients who underwent ACL reconstruction, quadriceps strength before surgery was the single biggest predictor of the level of function the patient would eventually regain. They concluded that quadriceps exercises to regain strength to at least 80% of the uninjured leg should be performed before ACL reconstruction to optimize chances for a successful surgery and return to previous level of function.

We suggest that ACL reconstruction should not be performed before quadriceps muscle strength deficits of the injured limb is less than 20% of the uninjured limb.

Eitzen I, Holm I, Risberg MA. Preoperative quadriceps strength is a significant predictor of knee function two years after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Br J Sports Med. 2009 May;43(5):371-6.

Conclusion

If you have been told you may need a surgery for your painful joint, don’t wait on this! Take action now to build strength and stability around your painful joint. The evidence is clear: building strength now can slow the progression of your joint arthritis, shorten your hospital stay if you do get surgery, and make your eventual rehabilitation more effective. And because strength training can be done in as little as 30 minutes, twice per week, you don’t need to upend your entire life to make room for a stronger, healthier body.