This is the second article in a series on strength training and POTS. It is not medical advice and is presented for informational purposes only. Consult with your medical provider before adopting any exercise program.

In my first article on Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome, I discussed in very general terms the nature of the condition, and how strength training can help manage POTS symptoms. Beyond addressing autonomic dysfunction and vulnerability to dehydration, a tension focused approach to strength training challenges the heart to beat harder, not just faster. This results in heart strengthening, which can improve cardiac output, one of the key factors involved in orthostatic tachycardia. In this article, I’m going to explain how tension based strength training can also help to manage POTS by improving another key factor: venous return.

Before we get deeply into the subject of venous return I want to again be very clear. The causes of POTS are diverse, from hormonal dysregulation, to impaired nerve function, to inadequate blood volume. In no way do I mean to imply that strength training alone could "fix" any of these issues. Nor do I mean to undermine the extensive therapies and treatments many people with POTS require to manage their conditions. Instead, I am simply interested in the question: "What can exercise do for a person with POTS to improve their level of function and health."

How does blood get back to the heart?

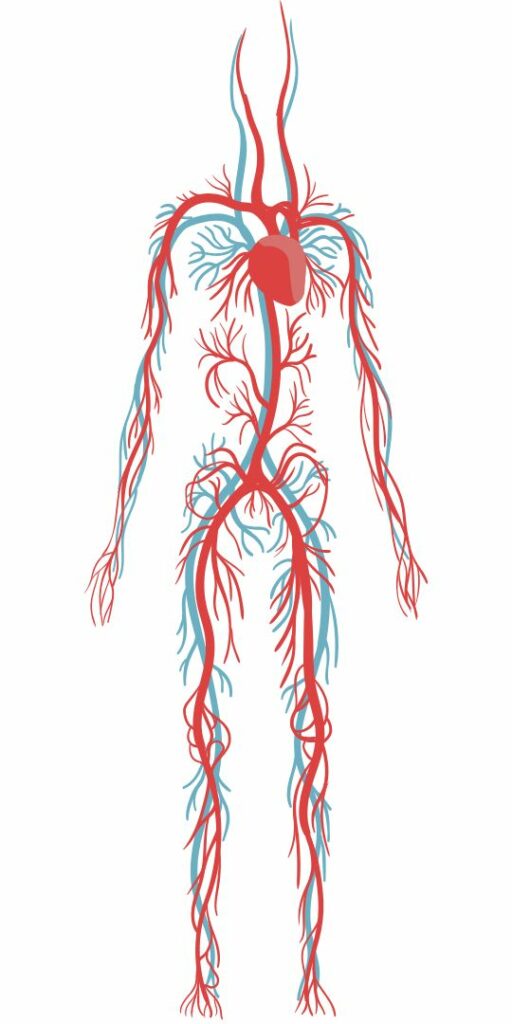

Venous return refers to the rate at which blood returns to the heart from the muscles. Our hearts push blood out to the organs and extremities. But once the blood is out there, the heart isn’t optimized to force the blood back up the veins of the legs against gravity. If you’re lying flat, you’ll be fine, because there is no gravity to fight. But when you are standing upright, you’ll need some help getting the blood out of your legs and back up to your heart. Luckily, our muscle mass can contribute significantly to venous return.

The muscles of our legs, and particularly our calves, are often called the “second heart,” because of their ability to pump blood back up to the heart. This works because our veins have one way valves that only allow flow in one direction. When a muscle squeezes a vein, the blood is forced away from the muscle, and the valves ensure it can only flow in one direction: back up to the heart.

Muscles are essential for pumping blood back to the heart when we are standing upright.

This muscle-pump action prevents a problem called venous pooling where the blood would pool in the legs, like water stuck at the bottom of a water bottle. This can be a problem for people with peripheral vascular disease, which is common in smokers, and those with congestive heart failure. But so long as you have healthy veins and connective tissues, and adequate muscle mass in your legs, the muscle-pump action works to prevent venous pooling by pushing the blood back up to the heart. This is our first clue that strength training could be helpful to manage POTS.

As an aside, this is part of the reason too much sitting is "bad" for us. When we are lying flat, our heart can manage circulation on it's own. And when we are standing up and moving, the squeezing of our muscles helps keep the blood moving. But when we are sitting, our heart has to work against gravity to keep our blood moving without the help of pumping muscles.

POTS often involves venous pooling due to overly “compliant” vessels.

People with POTS can be vulnerable to venous pooling and poor venous return for several reasons:

First, many people with POTS also have problems with connective tissue health, such as those with hypermobility disorders like Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (hEDS). When some component of the body’s ability to make collagen isn’t working right, all the connective tissues in the body are affected. We might first think that this impacts our joints, but even our blood vessels rely on collagen for their elasticity. If collagen synthesis is impaired, blood vessels won’t spring back to their proper shape when lots of blood flows into them upon standing. This tendency for a blood vessel to stretch under load is called compliance.

Too much compliance means that when gravity pulls the blood into our legs, our blood vessels may not hold their shape well, bulging and allowing the blood to pool, instead of holding their shape and conveying the pressure of the heart’s pumping to help blood flow back up the body. Further, the valves in those vessels may not work perfectly, allowing backflow, and further exacerbating pooling in the legs.

Autonomic dysfunction can also lead to overly compliant vessels.

Second, if the signaling pathway between the nervous system and the blood vessels is compromised, as is the case with Small-Fiber Neuropathies or other dysautonomia conditions, the blood vessels won’t constrict in response to a change in position. Without this reflexive change in the muscle tone in our arteries and veins, the vessels can remain in the same relaxed state they would use when we are lying down. And the result, again, is too much blood flowing into and pooling in the legs.

It appears strength training may have significant potential to improve symptoms related to dysautonomia. Adolescents with dysautonomia see an improvement in stamina after resistance training. And, it may improve parasympathetic modulation in middle-aged adults with autonomic dysfunction. This is another promising finding suggesting strength training could help us manage POTS symptoms.

Low muscle mass in the legs means impaired muscle-pump action.

Third, as I discussed in my past article, those with POTS are often found to have low heart muscle mass. Similarly, skeletal muscle mass can often be below average in individuals with POTS and/or hypermobility. And since the muscle-pump action is crucial for healthy circulation, it should come as no surprise that muscle mass is a predictor of the rate of venous emptying.

It doesn’t really matter whether hypermobility, autonomic neuropathy, or hormonally driven hypervolemia is the root cause of a POTS diagnosis. In each case, normalizing the strength and size of the muscles of the legs has the potential to improve the efficiency of the muscle-pump action in returning blood to the heart. I say “normalizing” because it isn’t necessary (or possible, for that matter) for us to build huge muscles to see benefits. Simply strength training to build a healthy amount of muscle for your frame could improve the muscle-pump action and help manage POTS symptoms.

Weak legs also predispose us to overly “compliant” blood vessels.

As I mentioned above, having overly “compliant” blood vessels can predispose us to problems of venous pooling, or poor venous return. It turns out that researchers have known for decades that muscle mass is a clear predictor of this compliance. If muscle mass is poor, blood is more likely to pool upon standing, and the muscles will have a tougher time pumping that blood back to the heart when we get moving.

This is powerful knowledge if you happen to suffer from any connective tissue disorder, such as EDS, where your blood vessels are predisposed to being overly compliant. Even though your baseline level of compliance in the vessels of the legs may be poor, anything you can do to restore optimal leg muscle mass can help to improve it, and thereby improve venous return to the heart.

One more aside is that POTS can be a temporary but frustrating side affect after any long term hospitalization or illness. The prolonged inactivity and bed rest is strongly associated with reductions in muscle mass, blood volume, and cardiac output. Even if your POTS is a short-term problem resulting from convalescence after illness, strength training to regain your muscle mass, stamina, and venous return could help manage your symptoms.

Building healthy muscle mass should be our priority.

Armed with this deeper understanding of exactly how leg muscle mass affects our cardiovascular system, our path forward is clear. Strength training in a joint-friendly manner is the most direct way to safely improve the strength and size of our muscles, while keeping wear and tear to a minimum. And because strength training can be done in a sitting position, using modern exercise machines, we can begin building strength to manage our POTS symptoms, even when our tolerance for standing is still very poor. Don’t hesitate to seek out a professional who can help you get started on your journey to a stronger, more resilient body!

Thank you for this practical and thoughtful guidance. People with POTS and hEDS often have some level of fear of strength training – too often earned through past experiences of pain, injury, inadequate support and misinformation. For me, consistent, intentional strength training with a qualified professional in conjunction with other behavior changes and therapies has greatly improved both my POTS and hEDS. My muscle is the best offense/defense I have. I started basically on the floor of the gym and sometimes I still spend time there 🙂 It’s not a linear road but it’s a meaningful one.

Thanks for sharing your success Lauren! I’m so glad you have a good partner in your goal to safely build strength!

This is great info… haha I’m also a Lauren 🙂 trying to creep my way into better leg strength even with EDS/POTS etc. such low muscle tone!! But so glad to see some guidance on where to start!